A SMALL GROUP OF POLITICAL EXILES AND STUDENT ACTIVISTS landed in San Francisco before 1910. Immigrants in this group consisted mostly of well-educated, activist students. Some had participated in reform movements in Korea. When those reforms failed, they became fugitives in their own country. Others were part of the resistance movement against Japan’s rise in Korea but fled when surveillance and persecution under the Japanese became unbearable. Many of these activists were educated in American missionary schools and were Christians. Once here, these political refugees and students became leaders of the Korean immigrant community. They had two key missions: to support the needs of the small and scattered population of Koreans in America and to fight for Korea’s independence.

Dr. Seo Jae Pil landed in San Francisco as a political exile around 1885. He was an outlier as most Koreans who came to the US in the late 1800s were merchants and ginseng sellers. After the March 1, 1919 protest in Korea, he led the Korean Congress in Philadelphia and other efforts to rally support for Korea’s independence. Seo was the first Korean to become a naturalized US citizen in 1890 and the first Korean American to receive a medical degree in 1892.

Source: www.jaisohn.com

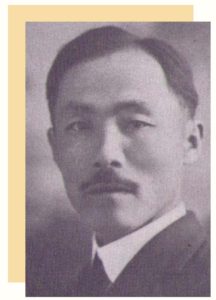

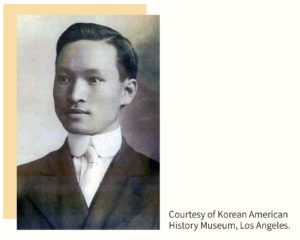

AHN CHANG-HO (PENNAME “DOSAN”) (1878-1938) landed in San Francisco with his young wife Hye-Ryun Lee (Helen) in October 1902. He had come to the US to study but when he saw the overwhelming needs in the Korean immigrant community, he set aside his plans to help his countrymen. Dosan is credited for establishing the very first Korean organization, the Friendship Society, in 1903, the first political organization, the Gongnip “Hyup Hui” Association, in 1905, and the Young Korean Academy (or Heung Sa Dahn) in 1913. He was a great educator and community leader. Dosan died in 1938, after being captured and imprisoned by the Japanese.

REVEREND DAVID (DAE WEI) LEE (1878-1928) landed in San Francisco as a student on April 22, 1903. Rev. Lee was the first Korean to receive a degree from U.C. Berkeley in 1913 and graduated from the San Francisco Theological Seminary in 1918. With Ahn Chang-ho and other leaders, Rev. Lee co-founded the earliest Korean organizations. He juggled multiple roles as the pastor of the San Francisco Korean United Methodist Church, president of the Korean National Association, port interpreter at Angel Island, and editor and publisher. He also invented the Korean keyboard that allowed for faster printing of the Shinhan Minbo newspaper beginning in March 1915.

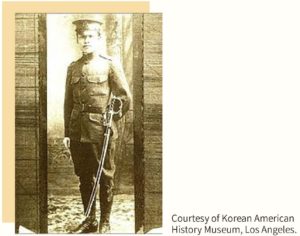

PAK YONG-MAN (1881-1928) arrived in San Francisco in 1905. He lived briefly in Denver, Colorado, then moved to Nebraska to study at the University of Nebraska. From very early on, Pak’s core belief was that Korea’s independence from Japan could not be achieved without military action. He devoted most of his life establishing military academies and training young Korean cadets in the US and in Hawaii. He was a key leader of the Korean National Association and served as the editor of the Shinhan Minbo in San Francisco in 1911.

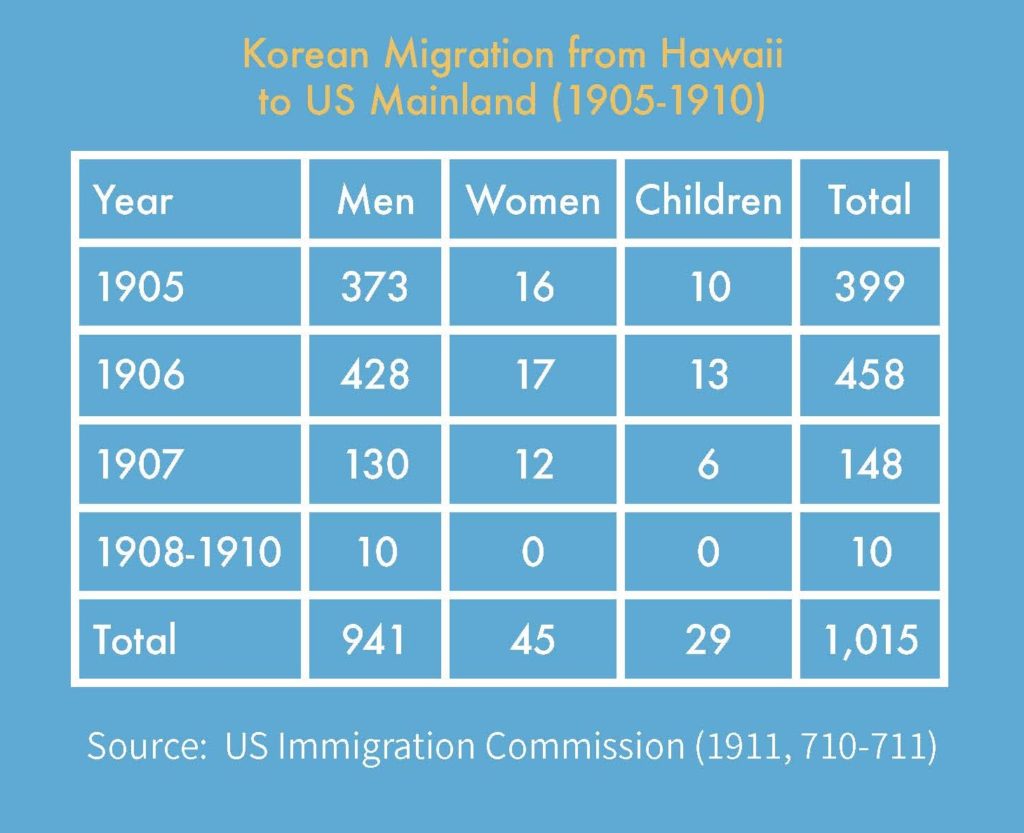

In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt entered into the Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan. Under the agreement, Korean and Japanese laborers were no longer allowed to transmigrate from Hawaii to the mainland.

ABOUT 1,000 OF THE KOREAN LABORERS WHO INITIALLY MIGRATED TO HAWAII, then a US territory but not yet a state, made a secondary migration to San Francisco between 1905 and 1907. The numbers dropped significantly after that because of the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Koreans from Hawaii came from a wide range of social and educational backgrounds but about 60% were illiterate. The main reason for their secondary migration was the desire for better working conditions. In Hawaii, they worked long, grueling 10-12 hour days on sugar plantations making 50 to 70 cents a day. In comparison, they heard that one could earn $1.00 to $1.50 per day working on a farm in California. Other Koreans had gone to Hawaii as a stepping stone to come to the mainland US.

“Working ten hours a day, I made five cents an hour which wasn’t much . . . [Hawaii] was only my stepping stone to America, and I had determined to work every day and save every nickel . . . to be able to go to San Francisco as soon as possible.”

— Easurk Emsen Charr, The Golden Mountain: The Autobiography of a Korean Immigrant 1895-1960, 125. Charr migrated from Hawaii to San Francisco in 1905 at the age of ten, and unaccompanied by any family.

“Father was desperate, always writing to friends in other places, trying to find a better place to live . . . he heard from friends in Riverside, California, who urged him to join them; they said the prospects for the future were better in America; that a man’s wages were ten to fifteen cents an hour for ten hours of work a day.”

—Mary Paik Lee from her memoir, Quiet Odyssey: A Pioneer Korean Woman in America, 10-11.

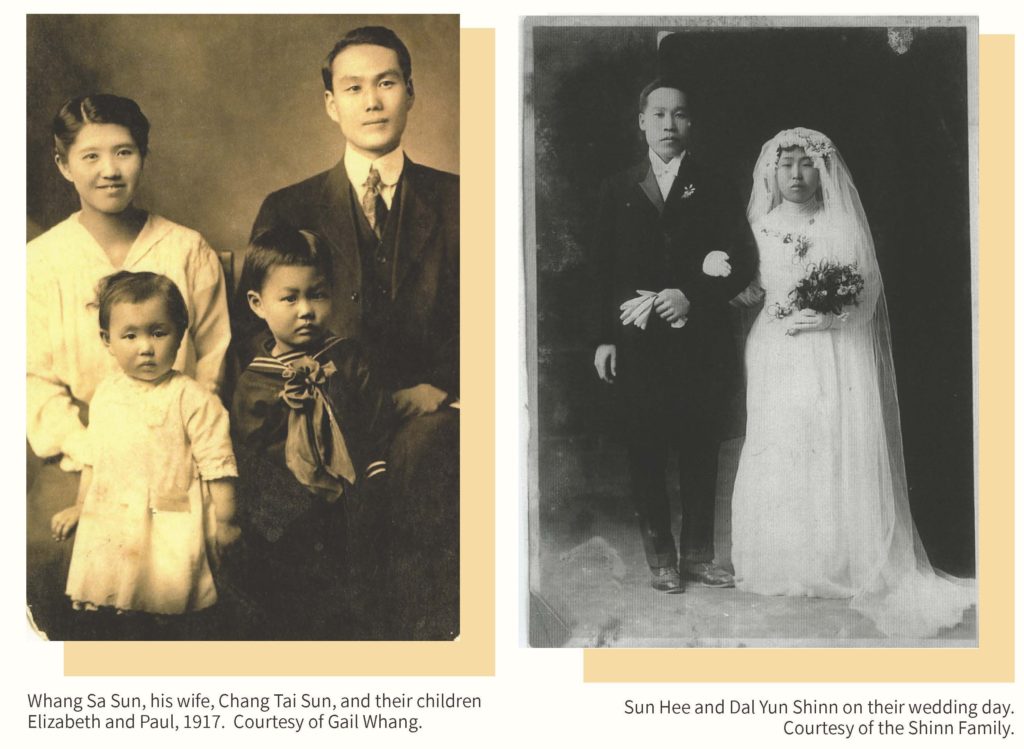

ABOUT 1,000 KOREANS LANDED AT THE ANGEL ISLAND immigration station between 1910 and 1940. The immigration station had opened in 1910, the same year Japan annexed Korea. Many Koreans arriving at Angel Island were fleeing from the persecution and repression of the Japanese colonial government. The Koreans at Angel Island consisted of students, mostly young men in their twenties, family members of residents already in the US and “picture brides.” These were the few exempt classes of immigrants that were allowed under the US immigration laws that were increasingly hostile to Asians. For many Korean “picture brides,” marrying a prospective husband who they had met only through photographs was not only a way to fulfill their traditional obligation of marriage, but also a way to escape poverty or to continue their education.

“Wearing American clothes as a disguise, he and his wife, Chang Tai Sun, in the dead of winter, crossed the dangerous Yalu River, made even more perilous because it wasn’t quite frozen. From Manchuria, they traveled to Shanghai after changing into Chinese clothes because they were pretending to be Chinese from the remote Pokgun Province in Northeastern China . . . From Shanghai, he and his wife took a ship, the SS Siberia, and arrived in San Francisco on April 21, 1913.”

— From Memories of My Grandfather, essay by Gail Whang, the granddaughter of Rev. Whang Sa Sun.

“Sun Hee Shinn came to San Francisco as a ‘picture bride’ in 1916 to marry Dal Yun Shinn. Ahn Changho introduced the couple through an exchange of photos.”

—From the Shinn family history written by members of the third generation Shinns.

Because the Japanese imposed a strict travel ban on Koreans in Korea, many of the Angel Island immigrants had to leave secretly, often through the Northern border to Manchuria, disguised and assuming the name of a Chinese or a Russian person.